A guest lecture by Viivi Lähteenoja, PhD researcher at the University of Helsinki Department of Practical Philosophy and visiting researcher at Aalto University Computer Science.

The Many Faces of Consent

I’ve been thinking about consent recently and, it turns out, consent is many, many things.

Consent is the form you sign before a researcher attaches electrodes to your body in order to carry out a scientific experiment. This is because consent is the cornerstone of research ethics.

Consent is what you do when you sign any legal contract, like to buy a house or to take a job. This is because the entire corpus of contract law revolves around consent.

Consent is the permission you give your doctor to inject you with a vaccine. This is because consent is the foundation of medical ethics.

Consent is the form you sign so that your kid can go on a field trip with their school class. This is because children are not considered mature enough to make such decisions on their own.

Consent is understood to be mandatory in sexual activity. This is because feminists and other activists have fought to make that the prevailing cultural sentiment, at least in this part of the world.

Personal Sovereignty

The importance of individual sovereignty is nothing if not increasing in modern, liberal-democratic societies. And consent is at the core of that sovereignty. Consent is about exercising agency over one’s personal matters. Consent is about allowing or denying a course of action that affects oneself, which brings us to why we’re talking about consent at a digital ethics course.

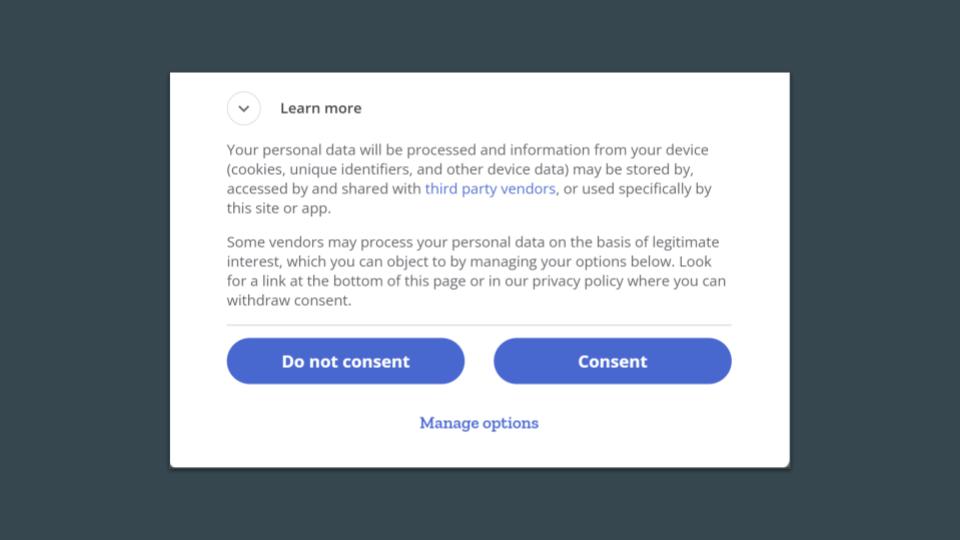

So, in addition to everything else I just mentioned, consent is also the button you click to get rid of the cookie popup on a website. This is because consent is required for legitimate personal data processing under the GDPR, which is the EU’s data protection law. And why does the EU’s data protection law require consent for data processing? That’s because the law is designed specifically to protect our personal sovereignty. And that’s the consent that I wanna focus on today: consent for personal data processing.

Consent as Moral Magic

Philosophers sometimes say that consent is a kind of moral magic. It’s a kind of magic that turns organ harvesting into organ donation. It turns battery into an ice hockey tackle. It turns theft into a loan. It turns slavery into employment. It turns kidnapping into a Sunday drive. It turns trespass into a dinner party. It turns assault into BDSM. And it turns personal data processing from surveillance into a service. As a general rule, it turns something that is not okay, into something that is okay.

I gave all these examples of consent, and we all have an intuitive sense of what consent is and isn’t, and especially to women and to queer folks, consent can be a very viscerally experienced concept.

Gate & Rope: Theoretical Perspectives on Consent

But what do theoretical philosophers say about it? They would say that consent can transform the normative expectations that hold between people – as long as the consent is properly given. And by transforming normative expectations we mean that consent can change what we are morally entitled to expect, or morally obliged to expect.

In other words, consent can work like a gate you open to allow someone to enter, or it can work like rope with which you bind yourself to an activity or another.

You consent to someone taking your bike on a road trip, you open this gate for them to take this action, take your bike with them. At the same time, this someone is bound by your consent to bring the bike back to you and in one piece, and you are morally entitled to expect that to happen.

Or you consent to deliver a lecture at a colleague’s course, you bind yourself with this rope of consent to performing that activity, to delivering that lecture. At the same time, your colleague is morally entitled to expect you to turn up at a time and a place and with a lecture to deliver – something they wouldn’t be entitled to expect without your consent.

So let’s dig a little deeper and apply this to personal data processing.

The Two Functions of Consent

The theory of consent says that it works in two directions:

- Requiring consent protects individuals from unauthorised invasions of their body and property.

- Granting consent enables individuals to engage in activity that would not otherwise be morally permissible.

I want to discuss both these functions of consent with regard to personal data processing. First, the idea that requiring consent protects individuals from unauthorised invasions of their body and property.

Is Personal Data Body or Property?

So, if consent is required to process my personal data, and consent has something to do with protecting my body and property, then which exactly is my personal data – body or property?

Is it somehow connected to my body and personhood, maybe as an extension of myself and my identity in the virtual world? Or is it more like my property, something I produced like a piece of music or a piece of code for which I own the copyright? One way to approach personal data and how it relates to a specific individual is to use the metaphor of data as labour.

The Data as Labour Metaphor

This way, can use the case of the moral magic of consent turning slavery into employment as an analogy of what’s going on when we consent to personal data processing.

Like labour, data is invisible and intangible – you can’t see it, you can’t touch it. Like labour, data is not strictly speaking a part of our body, but we use our body, including our brain, to generate data, just like we we use our body and our brain to perform labour.

And again like labour, data is not strictly speaking our property either, but it is valuable – so in the context of employment, we are usually somehow compensated for our labour, with a salary, with money. And in the context of data processing, we are usually somehow compensated for our data, with a service that’s free for us to use.

And like with our labour, someone else is usually making a ton of money for themselves with our data.

So remember, requiring consent protects us from the unauthorised invasion of something of ours:

- Consent protects our labour from becoming slavery by authorising others, our employer, to claim our labour for themselves in exchange for our salary.

- In a similar way we can say that, in theory, consent protects our data from becoming something morally not permissible like slave labour, because with consent, we authorise others, companies and governments, to lay claims on our data in exchange for services and a functioning society.

Enabling Organisations Through Consent

Ok, now for the second function of consent, which is really the same as the first one just from a different perspective: and that was the idea that granting consent enables individuals to engage in activity that would not otherwise be morally permissible. If we apply this to personal data processing, it becomes this: granting consent enables organisations to engage in processing our data that would not otherwise be morally permissible.

Does that seem correct to you? Let’s look at this from the point of view of the organisation, maybe a company, maybe a government, maybe a research institute like a university. Some organisation that wants or needs my personal data to do something.

According to this, what we have up here, this organisation is not morally permitted to process my data unless they have my consent to do so.

In the case of the research university, this seems pretty intuitive. Like we said earlier, informed consent is a cornerstone of research ethics. You can’t experiment with people, and collect data about them, without their consent. Not even in the name of scientific progress.

But about the case of the government? Why does it need my consent to process my data if all it’s doing is trying to ensure the delivery of basic services and a functioning society? Well, that’s not all that all governments always do. Some governments are corrupt, some are motivated by ideology that disregards the human rights of some or most of their citizens. Consent, again in theory, makes personal data processing by governments legitimate and morally permissible because I consent to the purposes for which it is done.

And finally, what about companies? Why do companies need consent from me to process my personal data if they need it to deliver me the product or service I pay for? Well, that’s not all that all companies always do.

Some companies collect my personal data, our personal data, in order to target us and to hurt us, or in oder to sell that data for others to target us and to hurt us – either directly or indirectly. And by hurting us I mean causing things to happen that go against our express wishes and desires, that contradict what is in our best interest, and that have a negative impact on our quality of life.

These harms and hurts occur sometimes on the individual level, things like:

- Manipulation into spending commitments one cannot afford or other unreasonable contractual terms,

- Bullying and harassment online and off, like doxxing and deepfake porn, or things like

- Persecution for engaging in the wrong faith or sexual behaviour, for acts of journalism or whistleblowing,

- Or identity theft that leads to financial and legal hurt and harm.

These harms occur too often. But much, much more commonly the hurts and harms from unauthorised personal data processing occur on the community or societal level.

These hurts and harms are things like:

- Damage to democratic systems and institutions via the spread of mis- and disinformation

- Harm to social cohesion and societal stability via fragmentation of the information landscape

- Divisive political polarisation and radicalisation via hate speech

- Damage to the rule of law via data-driven predictive policing

- Damage to the fair and competitive functioning of markets via monopolitic behaviours enabled by data hoarding

- Disregard for the human rights of specific groups and communities via unchecked biometric surveillance

- And so on.

It seems clear to me, that none of us would wish these hurts and harms for ourselves or others, yet we do consent to personal data processing. And that’s because personal data processing also contributes to the advancement of science, it also contributes to the functioning of societies, and it also contributes to the provision of products and services we all want and need.

So what are we to make of all this? Is personal data processing actually evil, since it’s capable of all these hurts and harms? Or is it fundamentally good, since it’s necessary for all these things we all want and need?

The Moral Neutrality and Non-Neutrality of Data Processing

Well, just like any technology, personal data processing is at the same time always morally neutral and never morally neutral.

Data processing is always neutral in that it can be used for both good or bad purposes. As we just said, the government can spy on you and infringe on your fundamental right to keeping what happens in your bedroom private, for example. Or they can keep records of your medical appointments so it can provide you with the best care possible. A company can collect behavioural data about you to sell onto malicious actors so they can most effectively exploit you. Or they can process your data in order to provide you with a personalised service that you want and want to pay for. That’s how data processing is always neutral: it can always be used for morally good or bad.

But data processing is also never neutral: it is always used for some purpose, and that purpose is always morally charged, and never neutral.

So it’s the moral of consent that, in theory, transforms that moral charge of the purpose for which data is processed from morally not permissible to permissible. And because of this awesome transformative power that it has, consent is sometimes requested in circumstances that do not warrant it, in circumstances where it cannot work its magic.

Let’s take cookie consent as an example of this, a circumstance where I argue that consent usually cannot be considered “valid” – a circumstance where what looks like consent actually lacks the transformative power, the moral magic, that it has elsewhere.

The Four Conditions of Valid Consent

Cookie consent fails or is likely to fail on all of the four moral conditions of valid consent: competence, voluntariness, knowledge, and intention.

For consent to be valid, it needs to be given by a person competent to give consent. But because cookie banners make no effort to ensure that the person clicking “I consent” is competent – whether they are a child, developmentally challenged, suffering from dementia, drunk or high, or otherwise considered not able to consent – the consent given cannot be reliably judged as given by a competent person.

Second, for consent to be valid, it has to be voluntarily given. Voluntariness means free from coercion: consent with a gun to my head is not valid consent. In the same way, much more benign threats can render consent invalid. Consenting to an “ad-supported” version of a service like Facebook because one cannot or will not pay for the “clean” version cannot be considered valid consent for data collection, because Facebook is for many in the world an essential means of communication with family and friends. More extremely, WeChat and AliPay are essential for anyone living in or visiting China. The data collected by these apps is incredibly extensive and there are many legitimate reasons to disagree with how the data is used, but life in China is not possible without them, rendering any consent to data collection by these apps invalid.

Third, for consent to be valid, one has to have knowledge of what one is consenting to. This is a big one for personal data processing, since arguably only a tiny fraction, if that, of consents for personal data processing involve adequate let alone comprehensive knowledge of what happens once consent is given (and often already before it, as trackers are often loaded on sites before the consent button is clicked).

Finally, for consent to be valid, it can only be given for the purpose for which the consenter intends it. For example, if I lend you my axe for you to chop some firewood but you instead use it to break into someone’s home, that consent cannot be considered valid and I cannot be held responsible for it. This is another major issue for consents to data processing, since we usually intend for the data to be used something like to deliver a service, but in many cases, it is in fact also being used for other things, or in fact primarily collected for an entirely other purpose.

In sum, even though we actively click on “I consent” on a website, that consent cannot in most circumstances be considered valid consent. And invalid consent no more counts as consent than an invalid vote counts as a vote. It has form but no substance. It lacks the moral magic that transforms an activity into a morally permissible one.

Limits to the Moral Magic of Consent

Although the moral magic of valid consent can transform the moral relations between two actors, the permissions granted or obligations created by consent are not necessarily overriding of all other moral considerations, or the most important thing morally speaking, even if the consent can be considered valid.

For example, the moral magic of consent will not work if the normative order against whose background it was given is morally bankrupt.

Remember that one of the functions of consent is rendering some course of action permissible by authorising it. I can ask you to consent to come to my house and use my kitchen to make me dinner. Your consent authorises you enter my house, go through my fridge, and use my cooking equipment.

But consider a mafia boss who asks you to consent to acting as their hitman and authorises you to carry out a hit on an enemy. You consent and carry out the hit. Does the moral magic of consent transform your activity into a morally permissible? In the context of the criminal organisation, the mafia boss does have the power and right to authorise you to carry out that hit. In that sense the consent is valid. But the normative order of that criminal organisation itself is morally corrupt, and that renders the moral magic of consent impotent. It cannot work its magic and transform your act into a morally permissible.

Similarly, it can be argued that the moral magic of consent for personal data processing will not work in the case of Big Tech companies and similar, because the normative order of surveillance capitalism against whose background it was given is morally bankrupt. Note that this is a different argument than the one about cookie consents. This is the argument that, even if the consent collected by these services were valid, that consent still wouldn’t be able to perform moral magic and turn Big Tech data processing into an entirely morally permissible activity. The predatory and exploitative Big Tech or similar data company who gets our consent to process our data for purposes that hurt us and harm us has no moral authorisation to go ahead with it, even though the rules of the game that is late stage capitalism permit it.

We already covered some of the individual and collective harms and hurts that data processing by certain data companies cause. Let’s add one more philosophical argument.

The Kantian Imperative and Data Processing

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant famously formulated his categorical imperative – the ultimate moral rule – as this: “Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means to an end, but always at the same time as an end.”

What he’s saying is that people should always be treated as worthwhile in themselves, that people should never be used as just instruments or means to get to some other end.

Now ask yourself: can you imagine a data company that would treat you and your humanity as anything other than a mere means to an end? In your wildest dreams, can you conceive of a data corporation in our day and age whose end and purpose is anything but the accumulation of wealth for its shareholders at your expense? A data firm to whom you and your data are anything but an object of extraction in the pursuit of profit?

And let’s remember the point of consent in the first place: it protects our body and property from unauthorised invasions and it enables activity otherwise not permissible.

So why do companies require consent to process personal data? Because otherwise it would be unacceptably invasive and morally not permissible. Just because we’re numb to it, doesn’t mean it’s not invasive. Just because we’re used to it, doesn’t mean it’s permissible. And just because we click “I consent”, doesn’t mean it’s morally transformed into anything else.

What’s Really at Stake: Your Time

What’s ultimately at stake here is your time. The more time you spend on an app, using a service, engaging with content – the more time you spend, the more data they get to hoard. What’s really at stake is the commodification of our most precious resource, time. When we think we’re paying for content, what we’re actually doing is giving away our attention and time.

From Analytic to Continental Philosophy

Now, a short meta remark. Up until now I’ve been speaking the in the language and register of primarily analytic philosophy. For the last part of this talk, I’ll switch gears a little and draw on more continental philosophy, 20th century French philosophy, and critical theory. This will allow me to challenge some of the things I’ve just said, and to illustrate the richness of philosophical theorising about consent.

But first, a philosopher joke. How do you tell the difference between an analytic philosopher and a continental philosopher? If you care about things like truth, goodness, beauty, and love, you’re a continental philosopher. If you have a job at a philosophy department, you’re an analytic philosopher.

Anyway, as a backdrop to this final part of the lecture, it’s maybe helpful to point out one other key difference between analytic and continental metaphysical traditions.

The Subject-Object Distinction

The analytic tradition has this basic metaphysical idea that there’s a clear distinction between the subject and the object.

So what this means is that a subject is a being that exercises agency, has conscious experiences, and is in some relation to other things that exist outside the subject itself. In other words, a subject is any individual, person, or observer. On the other hand an object is any of the things that is observed or experienced by a subject. So a subject is something like you and I, an individual, who observes or experiences an object, something that separate from us, the subject.

Makes sense, right?

Okay, so this subject-object distinction is something that the continental tradition tends to reject. More precisely, the notion of a unitary, autonomous subject is rejected as inaccurate or unhelpful. Instead, some thinkers say that the subject is merely an effect of power and institutions, an effect that is continuously constructed via processes of subjectivation. In other words, they take the subject to be a social construct, a social construct that is always shaped by ideology. This kind of understanding of the subject as a social construct then enables a new concept to take center stage of metaphysics: deconstruction. So instead of dividing up the world neatly into subjects and objects, understanding the subject as a construct allows philosophers to deconstruct it and so better understand it.

So what does all this mean for consent?

Continental Perspectives on Consent

So, 20th century French thinkers tend to focus on the inherent limits, paradoxes, and problems with the ways that consent traditionally defines things like personhood body and and property.

It’s clear that consent is a powerful tool for building and preserving humanity, bodily integrity, property, as well as the recognition that there exists something other than the self.

But, say the French thinkers, both in theory and in practice, consent also reinforces certain social norms and dominant power dynamics.

As we said earlier, the consenting person – the subject – must be free from coercion, knowledgeable, intentional, and competent to this or that degree, right? These things enable the subject to give valid consent.

But what these things also enable is that at the same time as valid consent is given by the subject, at the same time the subject affirms that any outstanding ambivalences, any minor or major hesitations, and any untidy or unruly desires that the subject may be experiencing are irrelevant as a matter of liability.

By consenting, the subject affirms that these things, ambivalences, hesitations, desires, that they don’t count, all that counts is the consent given.

But even if the traditional contractualist understanding of consent considers these things irrelevant as a matter of liability, this does not mean that they are irrelevant as a matter of ethics.

The “Cat Person” Story and Consent

Some of you might remember the viral short story called Cat Person, where the young female main character consents to sex with an older man to avoid having to navigate rejecting him once they’re already at his apartment after a date.

She considers the sex largely disgusting and goes on to ghost the man despite her resolve to end things politely but firmly.

The story is well worth reading as a vivid description of the moral nuance that can surround perfectly valid consent.

In addition, dominant analytic discourses of consent presuppose a subject, a person, whose desires, wants, and preferences are transparent and known to the subject themself, that they pull in exactly one direction and that they are unmistakable.

The Coherent Subject Problem

In other words, consent relies on the idea of the coherent subject—the self who is one self and the subject who truly knows their own mind.

This consenting subject is expected to remain consistent through time in order to engage in consent interactions. It must continue to be the same self that wants the same things, or at least knows when its desires have changed. It must remain the same self who once consented for that consent to have any validity.

Yet this very idea of the coherent subject is contrary to psychoanalytical insights of the unconscious and subconscious self. It’s contrary to the Marxist dissolution of the distinction between the individual and society, the distinction between the I and the we. It’s contrary to poststructuralist models of subjectivity as socially constructed and continuously in the process of becoming individuated. It’s contrary to biopolitical understandings of colonised bodies and their bodies politic as standing in perpetual dialogue with the oppressive political power of the coloniser. And it’s contrary to strands within queer theory and French feminist and poststructuralist theory that consider the subject as shattered by sexuality, eros, bliss, the sublime, or other transcendent experiences.

Consent and Liberal Political Theory

It’s also been pointed out that consent relies on and also itself enforces liberal ideas and ideals of the consenting subject and the subject itself.

The contemporary analytic idea of the coherent subject is considered to be the foundation of liberal theory of the social contract, and the rejection of this notion of a coherent subject is seen as grounds for rejecting liberalism entirely in favour of alternatives such as Marxism.

Consent as a Social Construct

And in addition to the subject being seen as a social construct, consent itself can also be understood as one.

Consent can be framed as a social, legal, cultural, economic, biomedical, technological, and literary construct.

If we understand consent as a construct in this way, we can see how it serves to create and to reinforce limits, boundaries, and borders.

Consent creates and reinforces boundaries between categories of social activity – that which is permissible and that which is not are separated by the boundary of consent.

And consent creates and reinforces borders between acceptable and unacceptable desires and acceptable and unacceptable social subjects.

In other words, consent is used to map and to regulate sexual desire and gender relationships, technological interfaces and data processing, relationships of production and consumption, and artistic interactions into that which is acceptable and that which is unacceptable.

Consent as a construct is incredibly powerful in this way: not only does it map what belongs to the realm of the permissible and what not, but it can regulate and police that things stay in their assigned space.

Conclusion: The Fundamental Fictionality of Consent

And as a final rebuke of traditional notion of consent, it can be argued that it is only after we soften our individual attachments to the sovereignty and agency that are falsely promised by consent, that it is only then that we are able to admit consent’s fundamental fictionality.

And with that, thank you so much and, if there’s time, I’m happy to hear your comments or questions.

Further reading

In the analytic tradition: Miller, Franklin, and Alan Wertheimer (eds), The Ethics of Consent: Theory and Practice (New York, 2009; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Feb. 2010), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195335149.001.0001.

In the continental tradition: Greenblatt, Jordana, and Keja Valens (eds), Querying Consent: Beyond Permission and Refusal (Rutgers University Press, 2018), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1vxm8b1.